I arrived in Puerto Rico on July 25th, the day corrupt Governor Ricardo Rosselló resigned after masses stormed San Juan. “Ricky’s” homophobic and misogynistic private messages were leaked to the public, yet he’d released an initial statement that he would not step down from office. So many protestors marched that a major highway shut down and cruise ships cancelled their stops to the city; until, at last Ricky relented.

When I stepped onto the cobblestoned streets, it was raining and cheers from marchers were audible over the deluge. Puerto Rican flags streamed above beaming faces, motorcycle rallies charged, and a joyous parade consumed the narrow roads.

Celebrations seen from my hostel balcony

My flight had arrived hours ahead of my companion’s. Kyrsten, one of my oldest friends from college, spontaneously made travel arrangements just a few weeks before to join me. Once I was settled in the hostel, I took my camera through Old San Juan, which unfolded directly outside of our door.

To me, the best part in touching down in another culture is seeing the patina and depth of age in walls and roads.

I see these wall “stickers” in older countries—my guess is to preserve the old walls and avoid graffiti. I love their impermanence and the casual application of glue, even the way they peel and how marks are added.

Even if wall mural “stickers“ help prevent tags, graffiti abounded during the protests. I ran into a middle aged man who caught me admiring a building, and he lamented the stains on his beautiful city. I saw lots of graffiti blocked out by white, just to be written over again. “Cabrón“ means bastard.

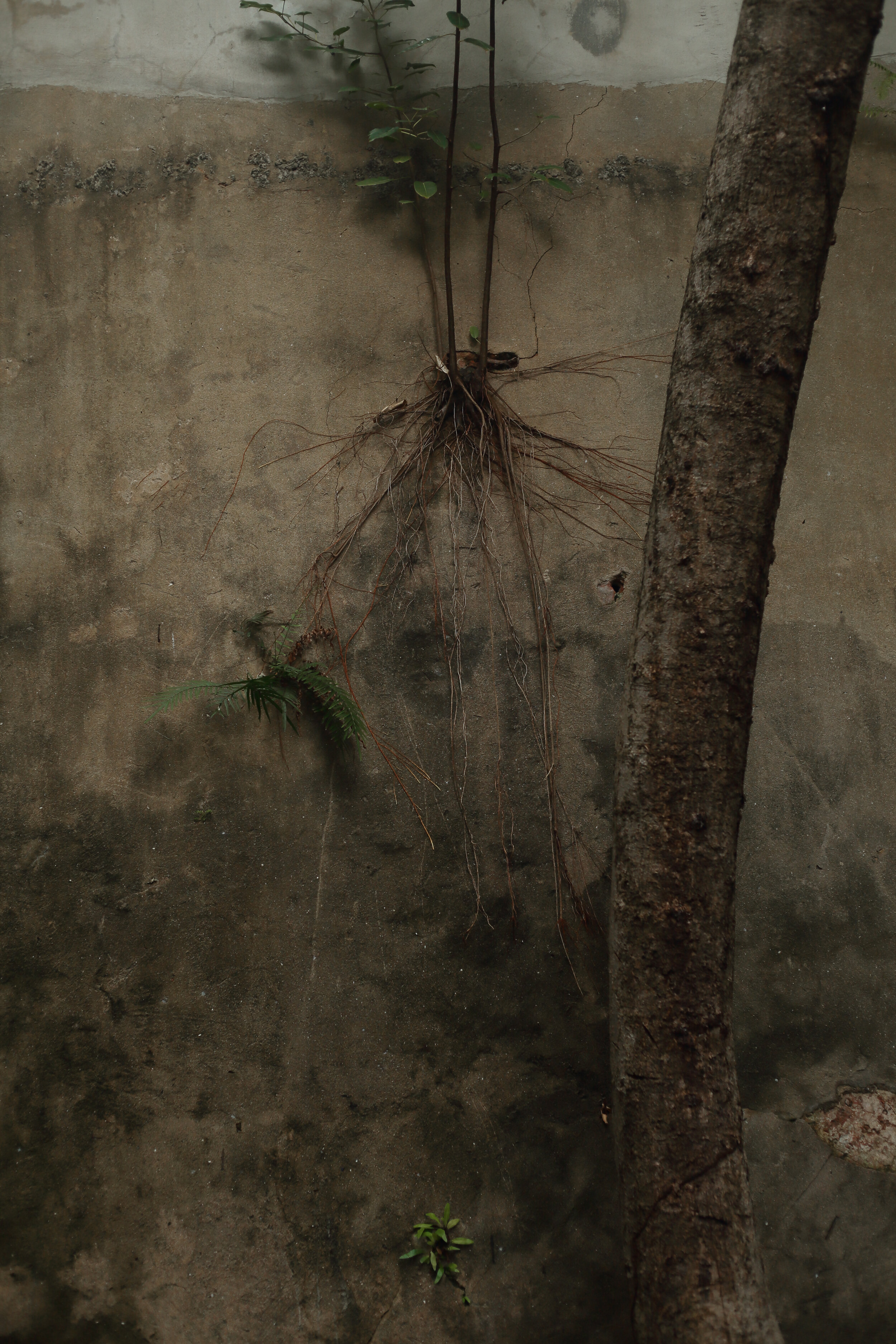

One observation about Puerto Rico is that the flora finds life everywhere—roots grow inexplicably in the middle of barren walls

Layers of age on a wall aside the water front

As I approached the mayor’s mansion at the crest of San Juan, I saw this police boat keeping guard of the mansion from the sea.

I walked through the fortified gates to where the celebrations took place just beyond the front of the blue mansion. Armed guards stood just behind the barricade and watched while people sang and cheered.

I was captivated by this young boy with a plastic Salvador Dalí mask. Later, I asked a local what Dalí represented here. He explained that there is a well known book, now also a show, called La Casa de Papel about a bank heist in which the robbers wear Dalí masks. Poor Dalí has come to represent the bad guys.

“Checkmate. We’ll clean house in the Capitol next” Wanda the incumbent was equally hated.

This street leading to the mansion is where the colorful umbrella installation had been displayed overhead. I overheard that they had been removed because the guards were prepared to use tear gas on protestors—the umbrellas were flammable and posed too great a risk.

At the north tip of San Juan there is a sanctuary for cats to come and go openly—they can run free throughout the island. Each was well fed, friendly, and had their left ear clipped to signal that they have been fixed. This was the only cat I came across that didn’t have a clipped ear.

Just outside our hostel on Calle Fortaleza. The tiled name of the street had been painted over in red with “Resistencia.”

The next day, Kyrsten and I rented a car and drove the 45 minutes outside the city to El Bosque Pluvial, El Yunque. Just outside the information booth there was a sign warning of rabid mongoose.

Once we were inside the rain forest, it took another 30 minutes to drive towards the summit. Many trails were still closed due to damage from María, but the windy trek to the very top was still open.

White Jasmine blossoms

A very loud kitten mewling his affections in the parking lot.

Flor de maga is Puerto Rico’s national flower and bares similarities to the hibiscus

One of the only stills I could capture of the enormous butterflies in El Yunque

Kyrsten’s purple hair matched the flora

Alien-like curlicues

One thing one shouldn’t do to one’s traveling partner is scream “OH MY GOD!” and point at something indiscernible ahead in an unfamiliar national rain forest. Especially when one’s companion is in an ankle brace. This dude was at least 8 inches long and as big around as a quarter. It’s hard to see here, but it has an enormous spine on the end by its tail.

View from the summit

The next day we ventured to Miramar for MADMI, El Museo de Arte y Diseño, a quirky little museum in a pink house with white scalloped trim. We saw the work of Nathan Budoff’s Diseñando Utopías—massive canvases of landscapes with bears, sharks, prairie dogs, and elephants.

The gallery at the end showcased abstracts in a high-ceilinged glass room with expansive beanbag chairs, upon which we promptly fell asleep and dosed for a good 45 min.

Next, we went to Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, a brick building that was once a school. Galleries encircle the grand central courtyard, which is open to the sky which. We entered Marta Pérez-García’s workshop, where she comes to teach museum-goers how to craft rustic dolls—she was absent that day, but the attendants showed us her shelves of material and mounds of dolls in various states of completion. Her collection critiques the physical and mental violence women face.

The main exhibit was of Antonio Martorell. Umbrellas in various forms were used as stencils on large sheets of paper that are hung in a grid. Part of the room is separated by open black umbrellas blockading your passage. They are tangled in red, white, and blue yarn and represent Trump’s wall. Beyond are historical texts declaiming freedom superimposed with portraits painted in bleeding marks like they were sprayed with water.

Apartments in Miramar outside the museum.

I love utilitarian details, unassuming sockets on outsides of buildings. These unvarnished moments are often seen as ugly (I think of grandmothers who sew scrunchy fabric covers for their electrical cords), but I like to discover their exposed presence as geometric compositions that serve as hints to a culture and its aesthetics.

Beautiful grime. Please don’t clean your base boards.

Aside from the ruins, the museums, the beaches, the hikes, the drum circle, the Bacardí tour, the brewery, the salsa dancing at La Factoría, the poetry reading open mike night, there was food. If I tell the story of this trip with images, the product is this post. If I tell the story of this trip with spoken words, the words are about food.

Mofongo is a classic Puerto Rican dish that consists of a brick of mashed plantains topped with any number of things: conche, pork, broccoli. It is a dense mass of pleasure and everyone eats it all the time. There were also enchiladas, tacos, empanadas, paella, pulpo gallego, ceviche, tostones, fried cheese with guava BBQ sauce (with which I feel in love), mallorca pastries, soursop mimosas, piña coladas, Puerto Rican brewed Ocean Lab beers...my stomach explored as much as my eyes.

At Esquina El Watusi, a bar that appears in Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown. This corner bar is surrounded by vivid murals and serves drinks with patterned paper straws. We drank rum with tropical juices like guava, tamarind, soursop, and passion fruit.

Mural seen from the corner of Watusi

On the morning of the 29th, we walked to San Cristóbal to learn about the fortress ruins that used to guard Old San Juan.

Views of María’s damage from San Cristóbal

Views of San Juan from San Cristóbal

The look-out tower here is called a garita, which is a symbol throughout San Juan. On our last night, Kyrsten had the silhouette of a garita tattooed on her forearm

This Garita Del Diablo is said to be haunted. A Spanish soldier named Sanchez disappeared one night when assigned to stand guard at this sentry box. It is the most remote garita in the fort, and the sounds of the crashing waves below would mask any calls for help.

Later on, when I was walking down the coast with this sight still in view, I talked to a local who told me Garita Del Diablo caused hurricane María. He also said that sharks only appear on this side of the coast, and that the rocky shoals there were most dangerous—swimmers get sucked inside and drown while the waves beat them against the rocks.

Detail of the stone walls inside San Cristóbal

Detail of ceiling

Views of San Juan from San Cristóbal

Views of San Juan from San Cristóbal

Hint of text beneath peeling paint on an exterior wall

I love that when a wall is updated, the pipes are painted along with it.

The following morning brought an intense warm rain. To the north, I visited the second fort of San Juan, El Morro. I brought along a disposable waterproof film camera. From the highest point in El Morro I could see the coast stretch to San Cristóbal, between which was a cemetery and a bright block of colors.

I followed the water and came upon La Perla, a slum impacted by María. Chickens run free here and every wall is a different vidid color. Trash was strewn in the roads and a young hen picked and swallowed styrofoam beads from a discarded package.

La Perla

Damaga from María

Detail from an exterior wall

Cats that followed me in the roads

This man on the boardwalk saw me admiring the birds. He winked at me and threw out this birdseed so they would scatter around me. He also brought out a chick that had been born that morning so I could pet its downy head. You can see San Cristóbal in the distance.

This is where the old man told me about the sharks that are seen along the water of La Perla because it is in sigh of la Garita Del Diablo. He said this is a skating rink that also turns into a pool for the youth there.

This is rusty metal showing through paint on a gate along La Perla's coast when you head north towards El Morro. I was so captivated I crab walked side-ways, crouching up and down, cataloguing across the boardwalk. This one looks like rockets of exploding roses to me. The images below relate to one of my previous projects, Esthesia, which explores our response to texture.

I tried to go to el Museo de Casa Blanca in the historic district, but the Ponce de Leon house museum was closed that day. I could, however, access the gardens behind. It was still sprinkling, but nonetheless I walked through the quiet pathways and admired the way mossy growths found life on their concrete surroundings.

Back in the historic district, I exited the gardens and began the trek back to our hostel.

Graffiti “White out”

56th st. Nunya Business

On the last day, I asked our hostel mates if I could take their portraits. This is Assal from Iran. She lives in LA and travels internationally every year for her birthday.

She sighed reluctantly when I asked her if I could take a photo. “I never like the way they turn out,” she said. “I look and I think, who is that?”

“Challenge accepted,” I responded. She liked the results and let me take multiple shots.

This is Richie in the laundry room under a sky light. I almost convinced him to bring in his teenage daughter for some shots (she’s signed by a modeling agency), but we couldn’t make it happen under short notice.

The hostel on Calle Fortaleza was comfortable—the location was key and we enjoyed its charm. In the kitchen there was an antique cast iron stove with decorative iron tendrils that we had to light with a propane tank and a lighter, on which we cooked breakfast burritos for a handful of mornings. Avocados in Puerto Rico were the size of squash and had smooth, un-dimpled skin. They maintained a bright green when they were ripe, and made their way into as many meals as we could manage.

Kyrsten and I shared a small room of two bunk beds with young women that first weekend, and were then the only occupants the rest of our time there. We each took bottom bunks and slept beneath scratchy white cotton sheets amidst a rattling air conditioner.

Our room was next to the only balcony that opened onto the streets. One night we were serenaded to sleep by a saxophone player on the street. On another, we were kept awake by an older occupant named Anne.

Anne was likely in her late 50’s, had great pillowy bags beneath her eyes, and the possibility of her arhythmic gait became a crippling limp when she knew you were watching. She was the kind of guest that assaulted you with unending monologues about the ingredients of her last meal while blocking your entrance to the bathroom.

The night Anne kept us awake was during a conversation with Assal. We couldn’t hear Assal’s soft responses, only Anne’s sharp, thunderous voice excitedly discussing her auras, and some “high level of security clearance” she had been awarded. Anne was to be avoided at all costs—her presence was deemed by all as unacceptable.

At one point a lawyer stayed at the hostel. He made his presence known from beyond our closed doors when he picked up his guitar and broke out into booming operatic song alone in the hallway…until Anne contested with a squall, her interchangeably defective legs audibly dragging the linoleum.

Richie, self-described as a “puffy man” while motioning a toke, was the only other presence. Though his uncle managed the hostel, Richie was on duty every shift we were there for except the first. Richie was from the Dominican Republic and also ran a small screen printing business. I bought a black shirt from him with the PR flag printed in white.

His dark dreads cascaded down to mid-thigh and his gummy smile was infectious--details that did not seem to be lost on Assal, who puffed out her formidable chest when in his company. She made him dinner on at least one occasion.

Assal and Richie were enjoyable company, and on the last night we shared some red wine in the small foyer and talked. Richie regaled us with tales of military grade “popper” fireworks he played with as a child in the Dominical Republic (which, regrettably, he hasn’t been able to obtain since), and about how his greatest wish was to see a manatee in the sea.

“I want to connect with it” he said, hands Egyptian-mummy-style crossed tight against his chest, “really hug it and look into its eyes, and communicate, ‘I love you.’ “ He also translated a poem about María I had found printed on a wall in La Perla.

“The hurricane, of course it was bad, but after it passed it made you see, really see your neighbors, and come together, no phones, nothing to distract you, to rebuild. We had dehydrated food sent to us in military packages—strange things. The worst was this philly sandwich with powdered cheese you had to add water to, plus no microwave or nothing. That was rough.”

Then Assal described her many travels; each year on her birthday she goes somewhere English isn’t spoken. Morocco, Egypt, Costa Rica (where she found the finest medical grade cocaine and laid solo and happy in a hammock singing and watching in fascination as her own hands danced in the air above her). She was now living in LA, worked at a farmer’s market, and commuted by bike. “Visit LA, and I’ll show you how to be. I know how to work the city, it’s best parts.”

Abruptly, Anne buzzed into the building and squinted up the steep steps at us in the foyer, worldless and furious, until Richie shrugged and went down to help her with some bags. Her limp was especially pronounced and she passed us by at a snail’s pace, immediate distaste for our congregation clear on her downturned mouth.

A few minutes after she’d been in her room, she limped into the foyer. “How long will you be talking?” she demanded. We stared back at her with no answer. “Because I’m meditating. I really need quiet for my meditating. I need you all to be quiet.” We said nothing, expressionless. She huffed back to her room.

“She can shriek all night on the balcony, but we can’t have a conversation? It was much later and we didn’t even ask her to be quiet, because that’s not what you do at a hostel. You put in your ear plugs and roll over and deal.” I said, Richie applauding. She had argued frequently about her amenities and had been a general pain to Richie and the guests.

She poked her fleshy nose through the slit of her open door. “Quiet,” she hissed. “When will you be all be done?”

“In a minute,” we said. Her nose retreated. She moaned dramatically from behind her door.

“Meditating,” Richie mused, and we laughed helplessly. Hostels are not strictly for the young, but they demand an easy-going outlook and an adventurous spirit. If you have neither, you don’t belong, and no one will care—those are the known facts, and I love the youthful spaces that are created by these attitudes.

The next morning, before we left for the airport, Richie was on the phone, scattered and on hold. “It’s Anne,” he said. She’d shut herself in her room. “She’s refusing to leave today, but her reservation is up. I’m calling the police to have her forcibly removed.” His eyes were frantic, darting side to side, “She has to leave!” he whispered.

I was devastated to depart without the end of Anne’s story.